At least a year before its release, I read a brief write-up that Ryan Coogler and Michael B. Jordan were cooking up a horror film. Cloaked in secrecy, I was unable to dig up much more than that, but found myself intrigued by the prospect. Considering neither one of them worked within that genre, I speculated about the possibilities having enjoyed their previous work together.

I’m always fascinated by directors and their muses. Scorsese and DeNiro, Lee and Washington, Burton and Depp. Coogler and Jordan have been on a roll with one another from the start of both of their careers and I expected at the very least to be entertained. Right before the film’s release, I got a whiff of the synopsis and rather snarkily asked my dear friend, respected entertainment journalist Kevin C. Johnson who happened to see an early screening, “Do we need a Black From Dusk Till Dawn?” His response: Yes.

I realize I was being reductive, but the similarities were obvious: two criminal brothers on the run, a roadhouse, a den of vampires. It felt a little too close to Rodriguez’s campy horror classic, but my curiosity overshadowed my skepticism and on Good Friday I slipped into the earliest matinee I could find. It’s nearly September, I’ve lost count, but I think I’ve watched the film five times so far, at least three times in the theater. It’s probably an understatement to say I’m enraptured by it, and it’s taken months for me to discuss it outside of my intimate circle of friends primarily because I don’t care to hear what the keyboard critics have to say and I don’t wish to waste precious time arguing about something that’s purely subjective. I wanted to live with the film for a while, allow the honeymoon phase to dissipate, sit with it, let it get under my skin, in my bones. I didn’t want hot takes, I wanted silence and analysis. Another close friend said to me recently, “This is when we really start to miss Greg Tate.” And that’s a fucking understatement. If Tate were alive, I would probably never write a word about Ryan Coogler’s SINNERS because I know his analysis would be so on point, so expansive and full that anything else would pale in comparison.

But here we are between the living and the dead, trying to bear the responsibility of the ancestors’ never-ending messaging. And that’s a part of what SINNERS is: an ancestral message, a spiritual channeling in the shape of an American horror film. When the theater went black after my first viewing, I remember thinking how proud I was of Coogler, Jordan, Carter, and the entire cast and crew of the film. I felt awe-struck and a little overwhelmed, knowing I watched something unique and transformative. Even with the preemptive comparison of From Dusk Till Dawn and its obvious skeletal similarities, I couldn’t shake scenes from the film from my mind, and as a longtime lover of horror – vampire narratives in particular –SINNERS is doing something with the genre that had yet to be explored on the big screen. The lion’s share of that being the unadulterated Blackness of the narrative, Black lore, ritual and tradition filtered through a vampire narrative. I still can’t help but speculate about Coogler’s sources; the filmography and bibliography that fueled the writing that became this screenplay. Spare me the obligatory Black syllabi. I want it straight from the horse’s mouth. Run the jewels, G. I need the plugs.

Even if I had them, there’s a part of me that thinks that much of what Coogler achieved (alongside his incredible cast and crew, of course) was done so through methodologies that extend well beyond reading and watching. At the risk of sounding woo woo, some things are created with ancestral assistance, memories that surpass the modern imagination, that travel through experiences and time periods that belie us. There are certainly other films that do this. (Haile Gerima’s Sankofa is definitely one of them.) SINNERS is standing on the shoulders of a number of cinematic ancestors, and we would not have this film without those that preceded it. In much the same way we would not have hip hop music without the sampled songs that preceded it. In some ways I do think of SINNERS as an amalgamation of a wide array of sources, both natural and supernatural, and it’s clear that Coogler is a horror fan who gets gore and gravitas, who can deftly move his eye from the bent backs of sharecroppers to the fangs of white consumption to the battles of Black resistance all while entertaining us wildly along the way.

For those not in the know, SINNERS is the story of Sammie, a young sharecropper with a deep love for playing the blues, explicitly frowned upon by his preacher father (expertly played by poet/musician/activist Saul Williams) who associates his son’s musical gift with the workings of the devil. Told in a 24 hour arc that opens with the story’s ending, the film is largely driven by the doubled charisma of Sammie’s twin cousins, Smoke and Stack, (hypnotically portrayed by Michael B. Jordan) who blow into town to manifest a dream of opening their own juke joint in a day.

It’s easy to think SINNERS is Smoke and Stack’s story. I mean, even the most staunch hater can’t deny the allure of the duplicated debonair of Michael B. Jordan’s performance. The camera moves between the cool, calculating smooth of Smoke and the smirky short-fuse of Stack through the length of the film. (One of my favorite early scenes is watching the twins slow flank Hogwood, played to smarmy excellence by David Maldonado, while negotiating the purchase of the mill that will be transformed into a den of iniquity in a day.) It’s easy to be seduced by the twins’ allure as they move together and apart throughout the story, but the tale is Sammie’s. It’s not the twins who are being (supernaturally) hunted. It’s him.

One of the earliest songs I was probably taught in church was “This Little Light of Mine.” I can’t remember learning it, but it’s buried deep in me, deep in most Black folks. Sung as a Christian anthem to children and adults as encouragement to not “hide their candle under a bushel” but allow their inner light to shine brightly in the world, “This Little Light of Mine” is an African-American mainstay passed down through generations. “Let it shine, let it shine, let it shine…” What they never tell you though is that all that shining can draw some pretty wicked shit from the dark.

Sammie’s light is sound. The minute he opens his mouth to sing in the car with his cousin Stack, everyone is put on notice. Equipped with a voice that belies his age and experience, murky and deep with the blues, Sammie’s voice and guitar possess the power to shatter time and space. Moving through the town with his cousin, collecting the necessary components for a successful opening – securing entertainment in the form of Delroy Lindo’s stunning Delta Slim and drumming up a crowd of willing sinners – Sammie is tutored in both the art of cunnilingus and the horrors of chaingangs, white exploitation, and the hauntology of American lynchings. (It took two screenings to clock the genius of Coogler’s sound work beneath Delta Slim’s harrowing monologue about the lynching of his friend. The first time I watched Slim break into humming to articulate and dispel his grief, I wept.) The lessons in Black sound in one fell swoop.

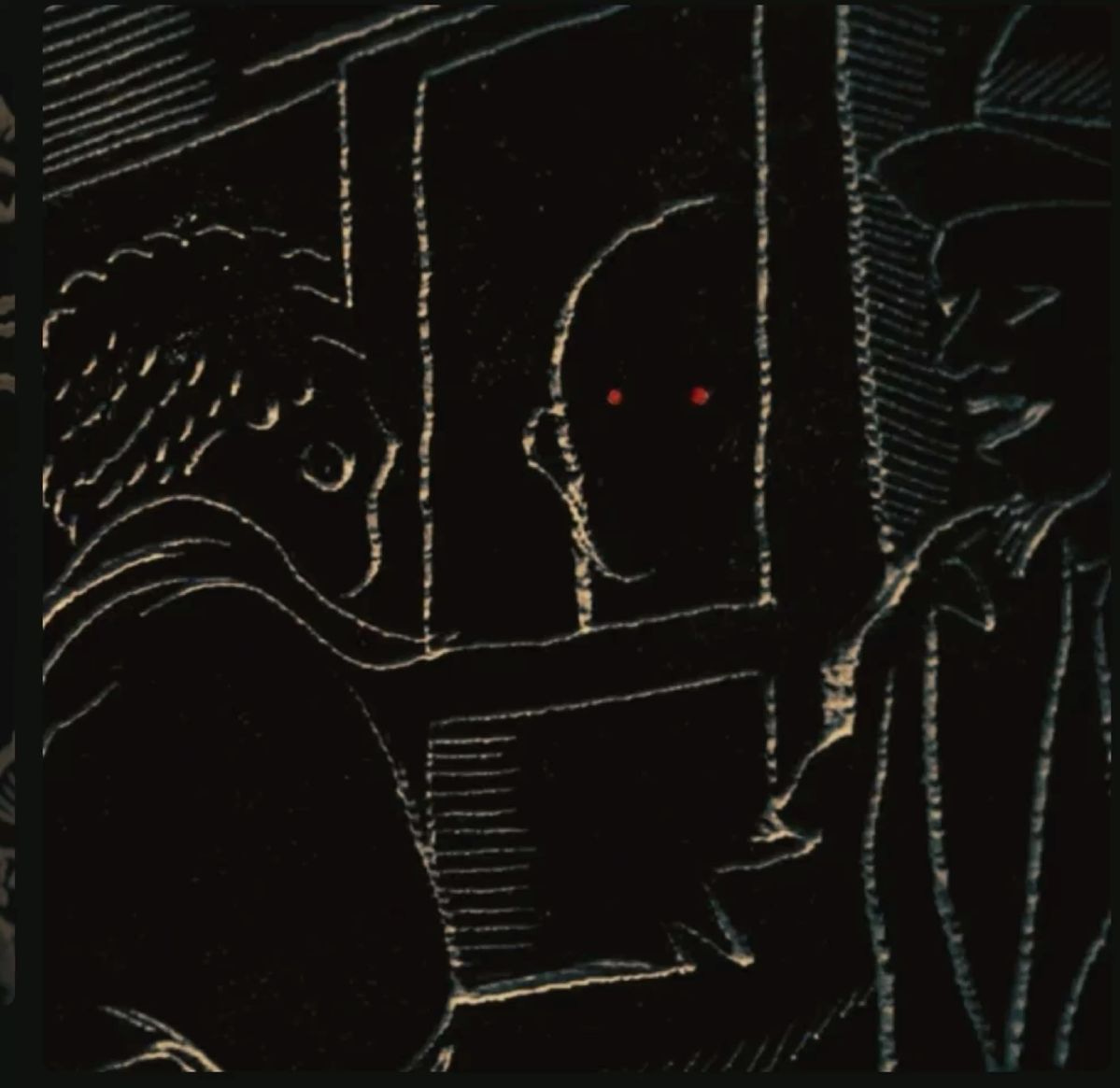

Speaking of fell swoops, enter Remmick, Coogler’s head vampire, who tumbles into the frame in flames from above. It’s difficult not to make the Lucifer analogy here. The devil himself, angel of Light, cast from the heavens with a posse of Choctaw hot on his trail. (There’s been much speculation and grumbling around the brief but powerful appearance of the Choctaw vampire hunters who enter the story sidelong Jack O’Connell’s Remmick. I’m not going to entertain it for long. The Choctaws’ brief appearance and failed warning of Remmick’s deception on the threshold of Joan’s porch is a powerful reminder of the existence of a people who preceded, who hold sacred and supernatural understandings and strategies for survival oft ignored and threatened. Their quick entrance and retreat from the narrative is significant.)

“Keep dancing with the devil and one day he’s going to follow you home.” Sammie’s preacher father warns him at the start of the story when Sammie comes to collect the guitar we come to discover is a treasured gift from his cousins. The origins of the guitar, with its silver sphere face, are shrouded in myth, its true backstory revealed humorously by Stack during the cousins’ day-long adventure. Originally believed to be a winning from a gamble with a famous blues musician, Sammie comes to discover that the guitar is a family heirloom that once belonged to his father’s abusive brother whom Smoke kills in defense of his twin. A guitar that once belonged to an uncle, a badman, a sinner, serves not only as the vehicle that unlocks Sammie’s spiritual gifts, but later in the narrative also the weapon that saves his life. Sinners and saviors.

Blues history runs deep. A thick roux of vice, Black erotics, violence, grief and death. Robert Johnson’s alleged deal with the devil swirls like smoke through Sammie’s tale. His preacher father’s warning is prescient but what he doesn’t share with his sharecropper son is the evil that courses through his own bloodline. An inherited guitar from a fratricidal son. The sins of the father are indeed visited upon the sons, and the battle of blood that Sammie’s songs kick off spans the length of generations.

When it comes to the cinematic history of the vampire, SINNERS’ Remmick is wholly unique. Most vampire narratives are set largely in European/white settings with European mythology and anxieties as their axis. Remmick crash lands in the Mississippi Delta’s Jim Crow south, surrounded by Black folks, Choctaw, Chinese Americans and, on the film’s periphery, whites. He brings with him a long bloodline with Irish origins. There’s a cloak of mystery and menace that shrouds Remmick. True to all vampires, he possesses a power of seduction in the form of a silver tongue (no pun intended) that he brandishes on anyone who comes within earshot. He sweet talks his way over Bert and Joan’s threshold with a sob story of being chased by Indians (true, but his reasons are not) and by the time Joan has dispatched the accused assailants, she is horrified to discover her husband has already been turned, Remmick placating her from a rocking chair in the shadows, a face dark and slick crimson. He uses his powers of persuasion throughout the film with argument and song frequently weaponizing allyship as a means of conversion.

Coming up in the pentecostal church from infancy until my early twenties, I can’t help but hear the missionary line whenever Remmick is in the frame. With Joan and Bert or without, his “everyday fella” demeanor and mouth full of proselytizations feel all too familiar. Not to mention the white boys I grew up around with Eddie Haskell smiles and a head full of ill intent. Remmick slowly infiltrates Club Juke’s opening night festivities with a gift of gab, a song in his heart, and an empty promise of brotherly love. But what hooked me was the shared history. Remmick’s argument for conversion has sinewy and horrifying roots.

I’m no historian, but suffice it to say, I know enough to remember that Black folks weren’t the only people depicted as monkeys and apes, and America, despite her rekindled fervor to white-wash her troubled past, has her fair share of “No Irish Need Apply” signs and worse when it comes to Ireland’s children. It’s this that makes Remmick’s character unique. Despite his ill intentions, his argument ain’t half bad; his blood-soaked plea of brotherly love launched from the shared platform of colonization holds up. If there were ever a reason to join forces with the dark side: the enemy of my enemy is my friend.

Blood is the business of all vampire narratives. Blood exchange, blood transfer. It even shows up in stories where there are no vampires (supposedly). Remember the woman in the Bible who Jesus healed who had an “issue of blood?” The sanctuaries of churches ring out with songs heralding the power of the blood of Christ. If they’re not singing about little lights shining, they’re warbling about the blood of Jesus. Revelations warns its readers about rivers turned to blood. According to the machines, the word blood appears in the King James Version over 400 times.

The implications of blood in SINNERS is multivalent. The blood ties between Sammie and the twins. Those between Smoke and Annie and their lost progeny. Mary’s one generation removed Black blood. The blood-rich soil tended and harvested by formerly enslaved Black people. The blood of Grace and Bo Chow’s daughter Lisa, who unbeknownst to her, serves as the match to her mother’s molotov that catalyzes SINNERS’ war into full bloom. But the blood that most captured my imagination was Remmick’s centuries-old ichor that carried untold generations of information and ire, and everyone exposed to it unleashes countless tributaries of genetic memory flowing between predator and prey. Talk about epigenetics.

The story is Sammie’s because it’s his blood that Remmick craves. Sammie’s ability to open the dimensions between the past, present, and future through song is a gift that the ancient Remmick covets. The metaphors are endless, some so obvious they border on trite. The bottomless historical consumption of Black culture by our caucasian counterparts, particularly through the DNA of the blues, so exquisitely rendered in Coogler’s Club Juke scene in which Sammie rends the veil of time and space, and metaphysically croons the juke into flames. (The first time I watched it, I burst into tears.) The white appetite to wholly swallow Black slang, fashion, attitude, culinary secrets, our bodies while categorically and violently rejecting our humanity and our rights to live free. This is the driver of Club Juke: the Stackhouse twins’ dream to carve a space of unabashed Blackness and liberation. FUBU. A free place, a chance to dance our way out of our constrictions. Club Juke heats up so bright the flames of Black freedom flicker hot in Remmick’s ancient eyes. He can’t stop until he gets a taste.

This is why I keep circling back to this Black vampire story. Remmick’s blood and its exchange. What is he trading? A circumscribed life for a fully free one. The ability to carry within you the memories of others as if they’re yours lived. The capacity to see what others have seen, to feel what has been restricted from you. Autonomy. Sovereignty. Power. The gift of time pumping through you.